Floor plans are the layout designs of a house drawn to scale. They illustrate the location of windows, walls, stairs, bathroom fixtures, room sizes, and furniture placement. Floor plans can also include outdoor areas.

Creating a floor plan is an essential part of interior design, architectural plans, and construction. It allows you to visualize the way your home will look – the room dimensions, its 3D interior design aspects, etc.

See What You Can Learn From a Floor Plan

Reading floor plans is second nature for an architect. It is the product of an education that stresses representation, both two- and three-dimensional, as a means to understand buildings and a way to convey ideas to others.

Reading floor plans can be difficult at first for nonarchitects, but this is a very useful skill to have, especially for those undertaking a project, be it a whole house or just interior changes. Floor plans are one of many two-dimensional drawings architects use (including building sections, elevations, and numerous details), but they are best for describing the size and scale of spaces, the relationships between spaces and the movement across a house.

A quick definition for those not familiar with reading plans: A floor plan is a diagram of a horizontal plane cut through a building, showing one floor. A plan is typically cut at about 4 feet above the floor, so as to include windows in the drawing.

Plans and other two-dimensional architectural drawings are orthographic projections, meaning that all elements are to the same scale. Therefore, no distortion occurs, as it does in perspective drawings, where objects receding in the distance are drawn smaller. Easy example: A plan of a cube would be a square.

See what can be learned by reading the following floor plans. The first few run through some basic concepts, also showing how plans can be articulated to be understood easier by architects and nonarchitects alike. These should help in deciphering the later examples. Hopefully greater understanding will lead to more floor plans finding their way.

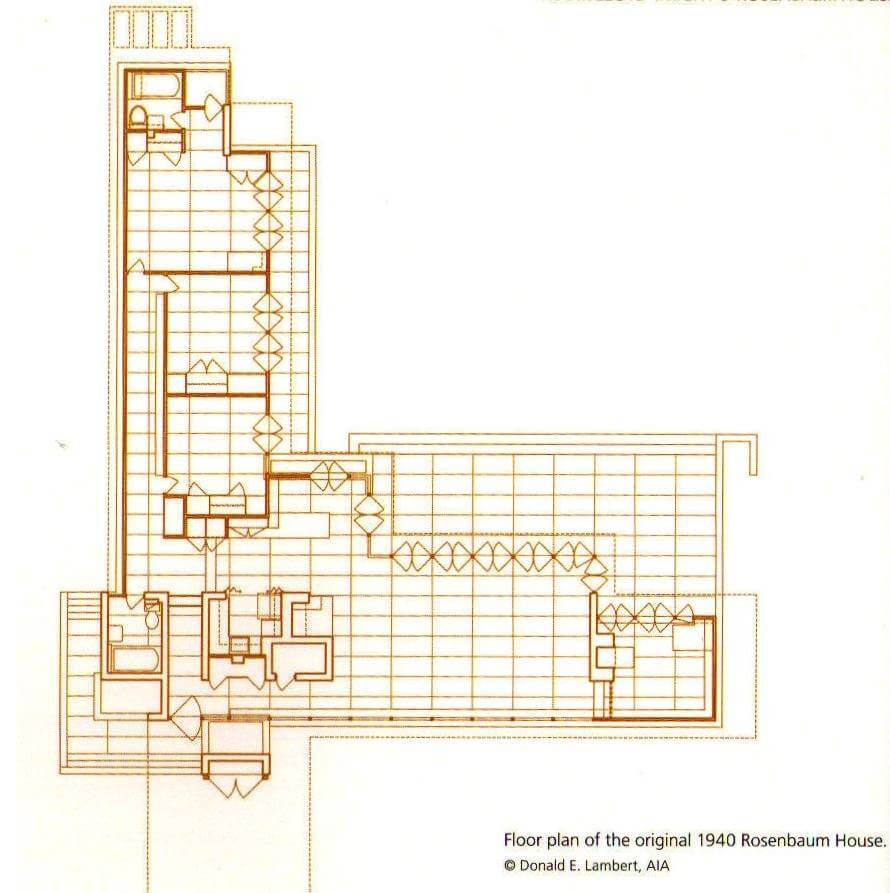

Many architects will readily admit that Frank Lloyd Wright created some amazing floor plans. The houses and other buildings he designed can be seen as means of giving materiality to his floor plans, which were spatially innovative. His fairly open floor plans seem mild by today’s standards, but they were many miles ahead of the Victorian norm of the time.

This floor plan is one of Wright’s Usonian houses, which he produced in the 1930s and ’40s. In the houses he used various shapes as modules; the Rosenbaum House is clearly based on a rectangle. By making the grid explicit in the plan (it would have been apparent in the floor pattern, but not as strong as in the plan) a couple things happen: The way other elements (walls, doors, steps) relate to the grid is apparent, and the distinction between inside and outside is blurred.

In the case of the latter, the floor and terrace blend together; only a row of door swings in the large living space indicate the boundary between these realms.

Before we delve into more floor plans, here is one variation: a site plan. The house is drawn with its exterior walls, windows and doors but without any interior elements. The focus is on the landscape and how the grounds relate to the building, particularly the means of access.

At the bottom of the drawing we can see a path to the front door, a path that extends into the private backyard and its series of terraces. It’s also evident that one can descend a few steps from the back terrace to a boccie court on the side of the house.

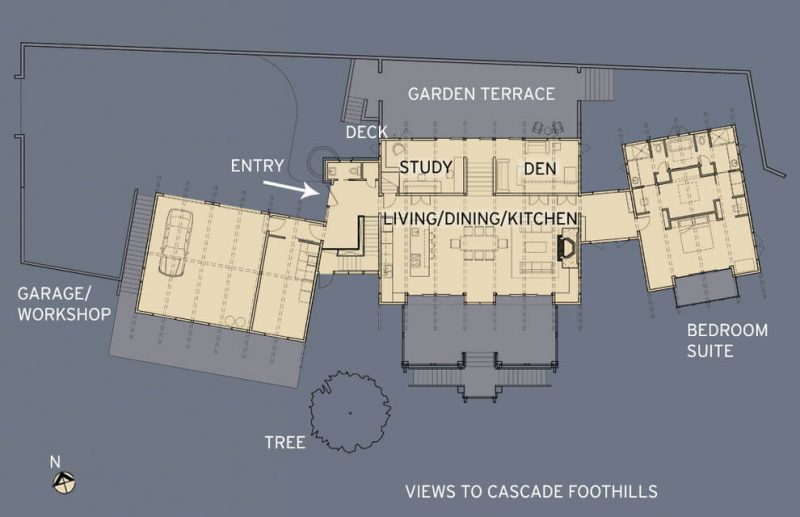

It’s easy to see how color improves the legibility of the previous drawing, but the same thinking applies to this floor plan, even though the focus is on the house, not the landscape.

Here, three colors distinguish three conditions, from dark to light: outdoors, in-between zones (terraces, covered patios), and interiors. By choosing a contrasting color for the last, the shape of the house — or more accurately the shape of the house’s parts — is very strong; it is composed of three rectangles linked by narrow bits of circulation.

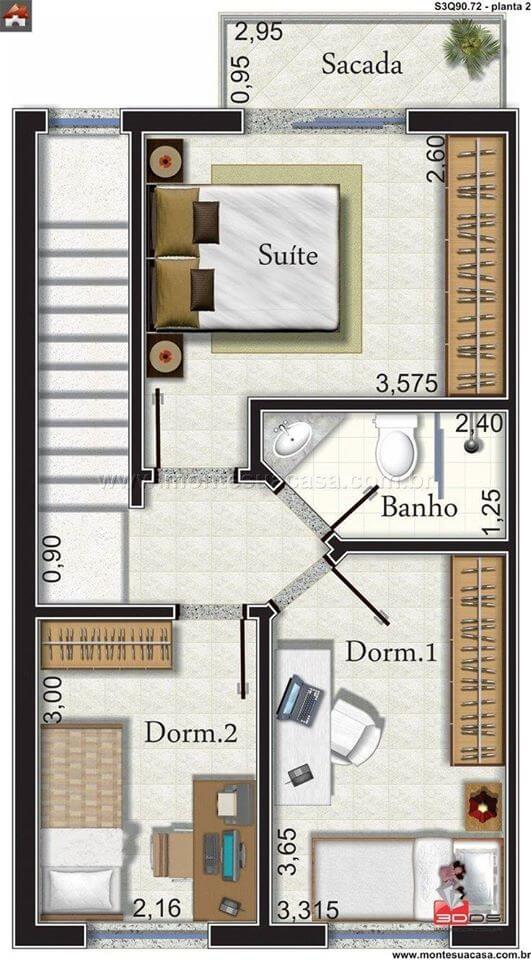

Another means of aiding legibility is to make the floor plan a three-dimensional drawing. This example does it so well that it’s very easy to see the horizontal plane that cuts through the house.

These 2-D/3-D hybrid drawings are easier with Building Information Modeling (BIM) software, which uses a smart model in the computer environment rather than lines, as in traditional drafting, but they suffer from one major flaw: They distort the drawings, so walls and other elements cannot be measured to scale. Nevertheless, they are helpful in envisioning a design and how the furniture fits into particular rooms.

While this house is too big for my tastes, it has a certain logic that makes the plan fairly easy to read, even with the 45-degree angle made by the garage. Directly above the left-right dimension (123′-10″) is the front door, behind which is a sizable foyer and an even larger great room beyond.

Running left-right between these two spaces is the hallway that organizes the house, a hallway that turns 45 degrees toward the garage. The central hallway makes this plan a double-loaded corridor, such that spaces line both sides of the spine.

Further, perpendicular to the hallway — the right wall of the great room — is the division between private (right) and public (left). The 45-degree kink may be derived from site constraints, but it helps to accommodate an extremely large master suite comprised of not one but two master bedrooms.

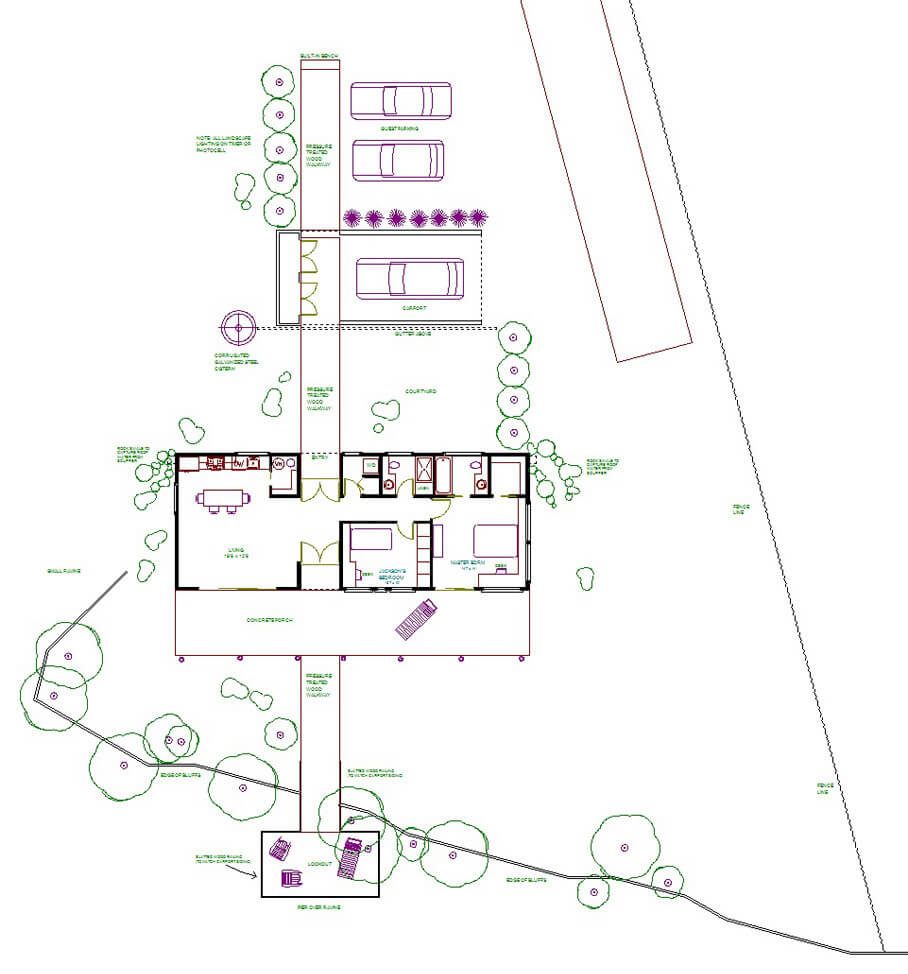

This house is aligned with my modern tastes, and it helps illustrate that a plan is an important determinant of a building’s style. The rectangular volumes of the garage, house, and lookout (from top to bottom) are linked by an external corridor.

This lets each volume exist as a platonic shape, rather than as a conglomeration of boxes, as in the previous example. The house volume here intelligently aligns the bathrooms and other service spaces away from the water, allowing views from the living area and bedrooms to the vista.

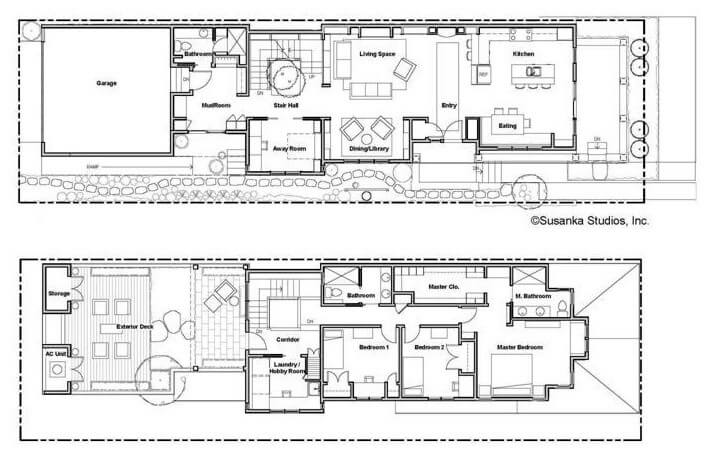

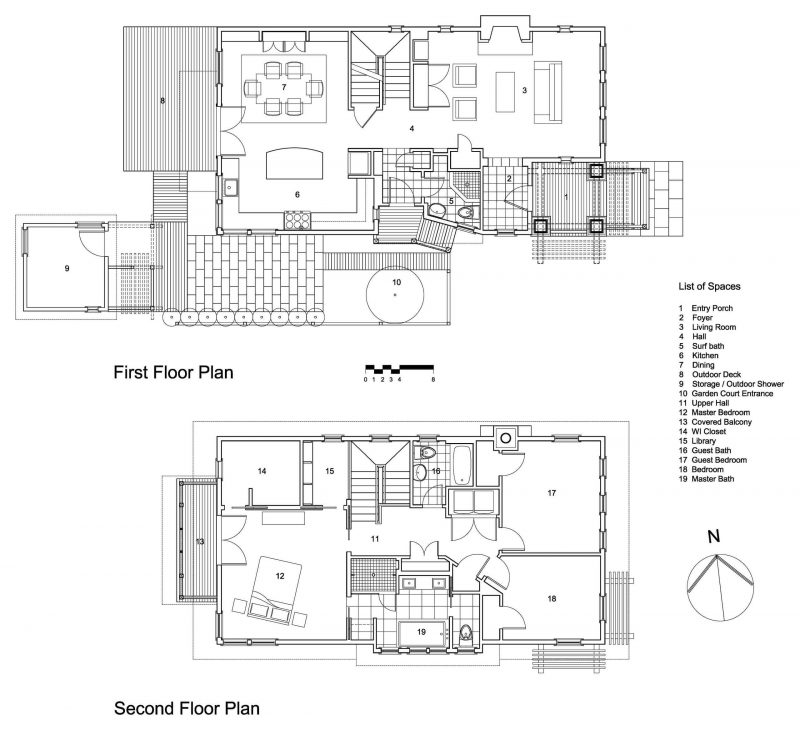

Of course, not all houses can be limited to one floor, so in this instance it helps to see lower and upper floors together. By placing one above the other, relationships between the floors can be grasped; the property line box in this example of one of Sarah Susanka’s “Not So Big Houses” is particularly helpful.

Here, the first floor is on top, and the second floor is below; the front of the house is on the right, so the garage visible in the top left sits off an alley. I find a couple things rather interesting in these plans: The front door’s location on the side of the house splits the living-dining-kitchen space into two, but instead of the living room located up front, it’s the kitchen, next to a covered front porch. Second is the way the roof of the garage is used as a deck.

Here is another example with a lower floor (top) and upper floor (bottom) together. While it looks like the second floor is much smaller than the first floor, they are both basically a rectangle of the same size; the first floor is drawn with detailed outdoor spaces (recall the Wright example earlier), making it appear larger.

Yet as the site plan earlier also showed, it’s important to articulate these exterior spaces, to design and understand how the exterior and interior realms relate. Compare this plan to the previous one, especially in the allotment of the living-dining-kitchen spaces. This plan is a bit more traditional, placing the public living space toward the front and the more private kitchen/dining space at the rear.

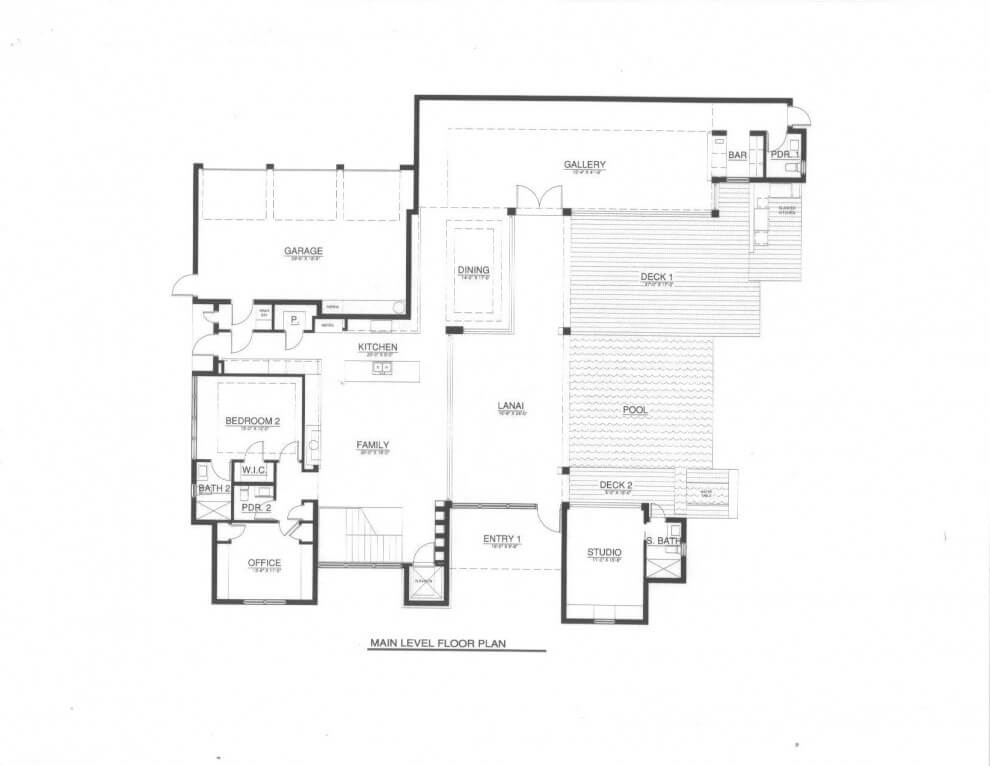

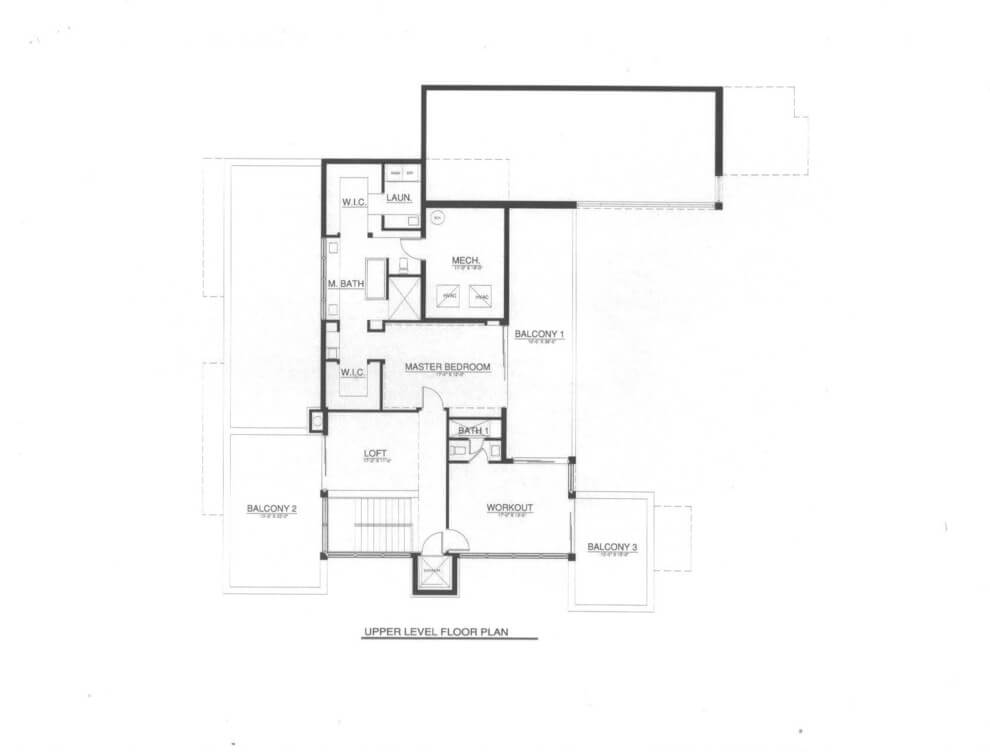

This last example splits the first and second-floor plans into two images — a little quiz if you will. This may not be an ideal way to read plans, but it often results in information being shared on the Internet.

Yet, based on the reading of earlier examples, a few things can help with orientation: stairs, columns, and major walls. The stairs are visible in the bottom center, columns are found in a line extending up from the entrance, and that wall at the top looks quite substantial. I’m most intrigued by the lanai — one enters a covered outdoor space before going inside the house.

Those three elements — stairs, columns, wall — are evident in the upper plan … kinda. The stair is still found in the bottom center, and the solid wall on the top indicates that the gallery is a double-height space.

But a few of the columns do not extend beyond the second floor; they support balcony 1, whose edge aligns with the line of columns. Yet the sum of these plans should be clear: This is an introverted house, focused on its large pool and deck space.

You must be logged in to post a comment.